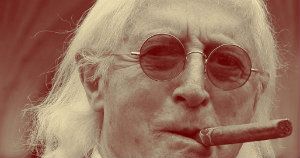

When Dave Lee Travis was released on bail last week he was keen to distance himself from Jimmy Savile in the public’s mind. Fair enough — to be accused of dolly-bird-groping rather than kiddy-diddling is probably a worthwhile distinction to make. But Savile and Travis go back a long way. The future Hairy Monster’s first job was at Manchester’s Mecca-owned Plaza Ballroom. He was only seventeen when the manager, Jimmy Savile, hired him as a trainee DJ. (His age wasn’t a problem because the Plaza didn’t have a licence to serve alcohol.)

The Plaza was just one of many dance halls and clubs that Savile oversaw, managed, disk-jockeyed at, wielded shadowy control over or had some kind of undeclared stake in, not only in Manchester but also on the other side of the Pennines — in Bradford, in Wakefield, in Halifax, over on the coast in Scarborough and Whitby, and especially in Leeds. In his hometown the joints he presided over included the Cat's Whiskers and the Locarno Ballroom in the County Arcade, known by locals simply as “the Mecca” (later rebranded as the Spinning Disc). That’s where, in 1958, his predilection for underage girls first came to the attention of the police. The matter was swiftly resolved by peeling a few hundred quid off the big roll of twenties that he always carried, right up until he died.

Meanwhile, in Manchester on any given night in the late Fifties and early Sixties, if you couldn’t find Savile at the Plaza at lunchtime, he’d surely be at the Ritz later on. Or, if not, try the Three Coins in Fountain Street. He didn’t even rest on Sundays; that was when he span the platters for upwards of two thousand jivers and twisters at his Top Ten Club at Belle Vue.

The man was everywhere — at practically every major dance hall and nightclub in the North’s heaving conurbations, as much of a fixture as the rotating mirror ball.

How did he do it? Criminally, it seems.

He’d started out in the early 1950s, putting on his pioneering “record dances” for any dance hall that would have him. Discreet beginnings, but he was soon Mecca’s “dancing area manager” in Lancashire and Yorkshire, and before the decade’s end he was a director of the company. Most of the fifty-two venues he ran were in the North, but not all of them. We’ll come back to that.

Dance halls back then were — much as today’s clubs largely still are — strictly cash-based operations. The books were easy to cook, and if Eric “Mr.

Miss World” Morley had given you the key to the night safe, it was even easier to skim the take. Is that how Jimmy Savile made so much money so quickly? We’ll probably never know, but he already had a Rolls Royce by the end of the Fifties and would soon be parading around the streets of Manchester in an E-Type Jaguar too.

How does that work, when he was still only supposed to be a wacky-haired weirdo who acted the yodelling fool and put records on for folk to shimmy and shake to? He already had his show on Radio Luxembourg by then, true, but it’d be another five years before he was a household name with regular appearances on

Juke Box Jury,

Thank Your Lucky Stars and

Top of the Pops.

A clue to just how much clout Savile wielded on the Northern nightlife scene fifty years ago is casually dropped by an anecdote in his official biography. One night he twigged that the doormen at one of his dance halls were operating some kind of scam. Savile went apeshit — not because his staff were contravening company policy, but because they’d had the gall not to include him in on it. He challenged them to explain themselves. He demanded his “cut” (yes, that’s how the official biographer phrases it), or they’d be out on their cauliflower ears. They acquiesced. Jim had fixed them.

Say hello to László

Hang on. Isn’t it supposed to be the heavies on the door who put the squeeze on the management? Not under Jimmy Savile’s regime. He had a whole crew of moonlighting miners, Eastern European bodybuilders — the one at the Mecca in Leeds was called László — and wrestlers at his permanent beck and call. Proper wrestlers they were, an' all, not mere dilettantes like Savile was during his stint as a novelty grappler.

One of the three wrestling Crabtree brothers, Shirley, was among them — then still a sheer cliff of muscle billed as Blond Adonis or Mister Universe, many years before he turned to fat and reinvented himself as Big Daddy. Whenever trouble broke out on the dance floor, Crabtree would pick up the miscreants, bundle one under each arm like rolls of carpet and carry them outside. "Yow've been naughteh boys. Very, very naughteh boys.” He mostly worked for Savile on the door at the Cat’s Whiskers in Leeds, and in 1965, when he launched a club of his own (or at least ostensibly his own) in Halifax, Savile duly pitched up for the grand opening.

Meanwhile, back under the glare of the brighter lights of the Mancunian metropolis, things were obviously very different. Oh, wait. No, they weren’t. It turns out that most of the doormen at Savile’s Manchester dance halls were not hardnuts from Harpurhey, Longsight or Ancoats, as you might expect. They were Yorkshiremen. Jimmy Savile had taken his crew with him for company on his trans-Pennine commute.

He kitted out the ones on the door at the Plaza with hair clippers to strip off any teddy boys’ offensive sideburns before they’d be allowed in. “Eether them sardboards go, or yow dow.”

Let nobody ever accuse Jimmy Savile of not running a respectable establishment.

What exactly is going on here? Being driven around in a succession of fuck-you flash cars, the big cigars, never spending two nights running in the same house, flitting from nightspot to nightspot with a posse of big-muscled minders, packing a big roll of banknotes to pay off the police, demanding and receiving tithes from his underlings’ illicit earnings.... What does all that suggest to you: the quirks and foibles of a wannabe showbiz personality or the typical trappings of a mob boss?

Beneath the veneer of a Mecca middle manager, it looks as though Jimmy Savile was running a large-scale protection racket at dozens and dozens of Northern dance halls and nightclubs for the best part of two decades.

A lippy little tyke with his hair in a tartan bob (Black Watch, as he liked to point out) is all that most people chose to see. But up North he ruled the night. How’s about that, then?

Smokeward bound

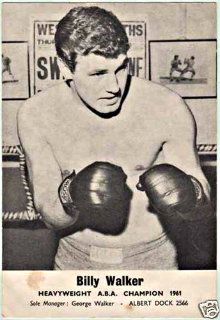

And not just up North. By the early Sixties he’d also secured what is now called a “significant presence” down South. One of the Mecca clubs under Jimmy Savile’s very-much-hands-on purview — he nipped down the A1 to DJ there on Monday nights — was the Ilford Palais. And although he didn’t take his Yorkshire bruisers with him for that gig, you can’t say he skimped on their substitutes. One of his doormen at the Palais was the boxer Billy Walker, who no doubt would have become the British pro-heavyweight champion had it not been for the immovable hegemony of Henry Cooper. Walker’s brother and manager, George, had been Billy Hill’s minder. If you can’t quite place the name Billy Hill, he was the Kray twins’ patron.

On his weekly trips to London, Savile ran a schedule as tight as when he was on his home ground back up North. Before heading out for Ilford, and perhaps to Mecca's flagship Locarno Ballroom in Streatham as well, he recorded his

Teen and Twenties Disc Club for Radio Luxembourg. Then he'd pop his head in at the offices of Decca Records. It was not a courtesy call. By the time he hit the street again, he’d not only replenished his stock of music but also fattened his wad. It was a sweet payola deal. He promised to play the latest Decca releases at all his dances in return for a reasonable consideration. Decca, like most other labels at the time, was very much a mixed bag in terms of the quality of their records (they famously turned down the Beatles, although they struck gold with the Stones soon afterwards). And for every future hit they gave Savile first dabs with, they saddled him with several real stinkers. He caned them all the same, one after the other at the start of his sets. Regular punters soon learned that they wouldn’t miss much if they arrived fashionably late, just in time for the decent stuff that they'd paid to hear.

Not the face!

Even the wrestling was bent. And not just because of the sham fights, with heels and blue-eyes working out all their moves in the dressing-room. The promoters were at it too. The top end of the business — because a sport is something it’s never been — was ruled by a cartel called First Promotions, which in turn was dominated by a tight clutch of Yorkshiremen. They bagged all the public’s favourite wrestlers and froze out any would-be rival promoters. Before long, the cartel was raking in £15,000 a week from TV rights alone. Of that, once “expenses” had been deducted, a couple of hundred quid tops would trickle down for the featured wrestlers to split between them. Jimmy Savile’s own bouts were promoted by Relwyskow & Green, two of First Promotions’ leading lights. By the mid-Seventies one of the Crabtree brothers, Max, was running the whole show.

We may never find out who Jimmy Savile really was: whether the entertainer, the philanthropist, the discotheque pioneer, the loner, the Bevin Boy, the loyal company man, the daft-coiffed eccentric, the secure-mental-hospital administrator, the all-in wrestler, the sociopath, the counsellor to royalty, the morgue attendant, the marathon runner or the serial sex fiend. At various times he was all those things. But it seems that from the early Fifties until at least the mid-Sixties he was, above all, a crook.

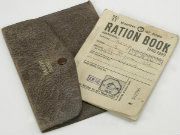

Within a very short time all the city’s rackets were under Spot’s control. He had a piece of pretty much everything that was illegal, illicit or just ill-regarded by society. His main strategic business areas were granting and removing bookies’ pitches at racecourses and dog tracks, protecting clubs and backstreet spielers, and — most lucrative of all — the black market.

Within a very short time all the city’s rackets were under Spot’s control. He had a piece of pretty much everything that was illegal, illicit or just ill-regarded by society. His main strategic business areas were granting and removing bookies’ pitches at racecourses and dog tracks, protecting clubs and backstreet spielers, and — most lucrative of all — the black market.  Within a very short time all the city’s rackets were under Spot’s control. He had a piece of pretty much everything that was illegal, illicit or just ill-regarded by society. His main strategic business areas were granting and removing bookies’ pitches at racecourses and dog tracks, protecting clubs and backstreet spielers, and — most lucrative of all — the black market.

Within a very short time all the city’s rackets were under Spot’s control. He had a piece of pretty much everything that was illegal, illicit or just ill-regarded by society. His main strategic business areas were granting and removing bookies’ pitches at racecourses and dog tracks, protecting clubs and backstreet spielers, and — most lucrative of all — the black market.